- Home

- Basic Piano Theory

- Bar Line

What is a Bar Line in Music?

This article may contain compensated links. Please read the disclosure for more info.

The music bar line is the vertical line that divides the notes in a score into groups. These groups are then called musical measures or bars.

What are bar lines in music used for?

Barlines are actually not extremely important in themselves (rather a bother at times), but they help us when reading music to visually divide the notes into groups on the music staff.

The grouping of the notes like this is determined by the beat of the underlying pulse of the piece.

The bar lines help us by showing where the most emphasized beats are: the first beat after each line. This is also called the downbeat.

Barlines are the vertical lines in a score.

Barlines are the vertical lines in a score.The Music Beat

All music is based on an underlying pulse or beat.

The beat can be steady and emphasized like in Rock music. Or not so obvious, or even steady, like in some Impressionistic music, for example.

The beat is what makes us want to dance and move to the music- or not!

Different rhythms are layered “on top of” the beat. This can be easy, simple rhythms or complex music rhythm patterns like in, for example, Latin music.

This beat (imagine the circles as a beat or pulse);

O O O O O O O O

is all the same. Try tapping with your hand a steady beat on the table or on your leg.

Now tap harder on some of the beats, like this (X marks the heavier beats):

X O O O X O O O

By doing this, the beats automatically seem organized in groups. In this case, in groups of 4. This is also called meter in 4!

Now try this:

X O O X O O X O O

This would make meter in 3!

And this:

X O X O X O X O

(-Not hugs and kisses!) Would make meter in 2.

So, what has all this got to do with bar lines? Well, bar lines are placed right before the X! Let’s swap the O’s and X’s with notes. Like this:

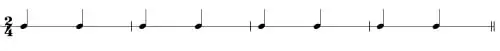

Hmm… just notes. There's no indication of the beat. So we add lines! This tells us that the note on the first beat after the bar line is supposed to be heavier or a bit louder ("downbeat").

But this example has a rather monotonous rhythm...

Each beat can actually consist of different rhythms. As long as all the note values add up to the same value as the beat.

Ready for Some Math?

We have to decide how much each beat is worth. This is pure math.

Let’s say each beat is worth the same as a quarter note (as above).

So, you could use any number of note values to add up to the same as a quarter note; for example, two eight notes, or four 16th notes, or a quarter rest, or two 16th notes plus one 8th note, etc.

The two fractional numbers in the start are the time signature. They help by indicating how many beats there are in each measure and what note counts as one beat.

For now, the quarter note or crotchet is worth one beat. (Yes, this can change!).

Here are a couple of examples:

Of course, most music does not only show the rhythm as above but also the music pitch.

Like in this example by Tchaikovsky (first Piano Concerto). Here the bar lines divide the music in measures with note values that add up to the equivalent of 3 quarter notes in each:

Different Types of Bar lines

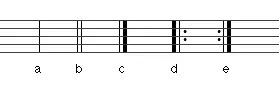

You will find a few different types of bar lines. In the music and at the end of the music. Here you'll learn what they are called and what they mean:

a. Simple barline: Divides the music into groups as we saw above.

b. Thin double barline: This is used to show different sections of a larger piece.

c. Double barline: This shows where the music ends.

d. Repeat sign: The dots on the right is used to show from where it should be repeated, if not from the beginning, let’s say a couple of measures in the piece.

e. Repeat sign: A repeat sign with the dots on the left is the most common sign used to show that the piece should be played from the beginning again.

Summary

By adding bar lines to a piece, we divide it into groups of beats. Even though we can’t really see the beats, they are (almost) always felt in the music. This underlying beat keeps the music organized, you could say.

- The bar lines divide the music into measures or bars, where the notes are grouped based on the number of beats in the measure.

- As we saw, each beat can have many different rhythms, or combinations of note values, on “top of” it. These rhythm patterns can be simple or complicated. As long as the note values add up to the same value on each beat.

- The grouping of beats into measures or bars (with the help of bar lines), is also called the meter of the piece.

Finally, the meter is displayed at the beginning of each musical staff as two (fractional) numbers.

The top tells us the number of beats per measure, and the bottom what note value has been chosen to represent the beat.

These two numbers are called a time signature! How cool is that!